FEATURE: First World War prisoners come home to UK at Boston

Arriving on January 7, 1918, with the end of the war still 10 months away, the group comprised 27 officers, 235 soldiers, and 370 civilians, including 16 of the 70-odd Boston fishermen who had been held overseas.

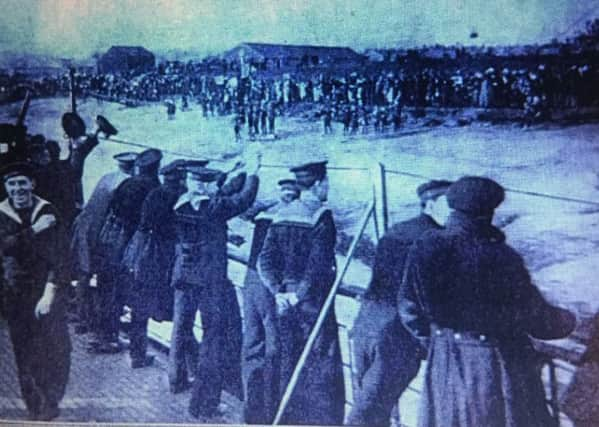

The Standard wrote that week: “The occasion was historic in the annals of Boston, and as the tenders came into harbour with their anxiously awaited exiles, the populace who lined the banks cheered long and lustily, to which a rousing response was quickly forthcoming from the boats. Fisher folk and others endeavoured to recognise friends or relatives on the decks of the crowded tenders. Two old ladies in aprons and shawls were wildly waving flags, to which they had themselves fixed the words, ‘Welcome Home’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThree Dutch ships (the Sindor, Koeningen Regentes, and Zeeland) brought the party from Rotterdam to the UK, dropping anchor at Boston Deeps. The prisoners then completed the last six miles of the journey to Boston Dock on four smaller crafts (Earl Roberts, Nimble, Frenchmen, and Marple). It was bright and sunny, but bitterly cold, The Standard noted.

Anyone imagining touching scenes of families reuniting with their loved ones at this point, however, would be wide from the mark.

As The Standard explained: “The entrance to Boston Dock was in charge of military police, with instructions to admit only those persons armed with a special permit, and their passport had been so sparingly issued that even the nearest relatives of soldiers who have spent many weary months in German prison camps were unable to obtain a glimpse of the son or brother from whom they had so long been parted.”

In fact, despite a ‘considerable number of journalists representing London and provincial newspapers’ descending on the town for the homecoming, only four press photographers enjoyed the privilege of seeing what took place (and even then they were required to promise not to talk to returning troops).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was, however, a civic reception, with the Mayor of Boston Ald A Cooke-Yarborough, the Macebearer, and some dock officials present at the quayside.

After the tenders had passed into the dock, the soldiers disappeared from public view. ‘Cot cases’ were transferred to trains for transport to either London or Nottingham.

“Relatives of a wounded officer here for three days, father, mother, and two sisters, vainly begged for permission to enter the dock,” The Standard wrote. “At least one of the family might” they suggested “be allowed to take a message”. They had to be content with a distant view of the sadly shattered lad across two sets of lines at the railway station and a few hastily flung messages. For four hours he had been within a few hundred yards of them, but on the other side of the wall. It was tantalising, but at least they were able to find out the hospital to which he was going.”

For the civilian prisoners, there was one more obstacle to overcome before reuniting with their families.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe group were first directed to the Institute of the Missions to Seamen, just outside the gates of the dock, where they were examined by Home Office officials in order to ‘make sure that they were bona-fide British citizens’, The Standard explained.

It continued: “All were heartily cheered, but a perfect roar of delight went up from the crowd, chiefly women and children, as the first couples of the released Boston fishermen came in sight and there were many touching scenes of reunion. Special constable and others were keeping the people back, but one young girl, Miss Ivy Parker, who caught sight of her father (William Henry Parker, skipper of the trawler Wigtoft) broke through the cordon, dragging her little brother with her, and both flung themselves simultaneously into the eager arms opened for them, while the crowd cheered.

“Then the Boston recognition became more frequent and the burst of cheering almost continuous. A discharged seamen pushed his way through, caught one of his children and put it over his shoulder, took two others by the hand, and with his wife carrying the fourth, strode off in the direction of home for what he said was to be the best dinner he had tasted for three years.”

Boston had sent more than 34 tons of food in parcels as well as clothing to Ruhleben, the German civilian Prisoner of War camp where the fishermen had been most recently been interred.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn appeal set up by a Mr Royal and a Mr Woodthorpe had raised £3,100 (about £161,000 in today’s money, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator) for the purpose and seen some 9,500 boxes of food put together.

Fishermen spoke about the life-and-death difference these contributions made (as well harrowing accounts from the Sennelager Camp, including an ordeal in which prisoners were driven to a rain-swept open field where they wandered for two days and two nights without food or shelter).

Frank Gale, of Seabank Cottages, Skirbeck, said: “We could not have lived without the extras.”

Mr Gale – who for a time kept the Napoleon Inn, at Skirbeck – gave the example of a Christmas Day dinner which comprised four potatoes about the size of walnuts. This was the official ration, but it was supplemented by boxes from home, he explained.

He said resources were scarce, in general, in Germany.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “We got a certain amount of information about the food conditions in Germany from the German wives of interred British prisoners, who themselves were glad enough to get food from our camp.

“We were told also that shoes and stockings could not be obtained without a police order, and then only on delivering the old shoes. One of our men, who was permitted to go to Berlin to procure certain materials, brought word on his return that large number of shops were closed. He did not see a single shop selling meat, game, or fish. Three days a week we had potatoes, and on one day a sort of soup made from a sweet kind of cattle marigold, cut up in small squares. This was boiled in water and a little fat. On Sunday, 10 pounds of meat were served out to make soup for 3,000 men.”

* Pictures supplied by Paul Meyer and John C. Revell, authors of Boston, Its Fishermen, And The First World War